Celebrating Native American Heritage Month 2022

Join us as we celebrate Native American Heritage Month throughout the month of November. The Rev. Leslie Scoopmire, our Missioner for Indigenous Ministry Engagement, has put together a series of short stories to help us understand and appreciate the role Indigenous Americans and their culture have played and continue to play in our lives.

We'll add new stories with different themes each week in November. We also encourage you to engage in discussion on our Indigenous Ministry Engagement Facebook page.

Click on the weekly headlines to read the stories:

November 1 - 7: Indigenous Leaders

November 1: Ousamequin (Massasoit), Wampanoag: Encountering Plymouth

Born in approximately 1590 in what is now Rhode Island, Massasoit was the grand sachem, or leader, of the Wampanoag people, who inhabited the coastal region of what is now New England stretching from Cape Cod to Rhode Island. After the Mayflower, bearing a small band of English Separatist families, arrived in what is now Massachusetts in December of 1620, they settled in the abandoned Wampanoag village of Patuxet, whose residents had been decimated by a plague introduced by European traders who had visited the area in 1616.

Ousamequin established a treaty of mutual aid with the Pilgrims, and maintained friendly relations for nearly 40 years until his death in 1665. With Ousamequin’s assent, Tisquantum (known to European history as Squanto) and other Wampanoags instructed the Pilgrims of “Plimoth Plantation” in techniques of fishing, farming, and cooking that enabled them to survive. Together, the Pilgrims and Wampanoags celebrated the first Thanksgiving in the fall of 1621—due in large part to Wampanoag contributions of five deer to ensure enough food for the gathered peoples. Ironically, the aid rendered in these early years of Pilgrim settlement sowed the seeds of the decimation of the Indigenous inhabitants of the region, which is why it is now observed by many Native peoples as a day of lament.

In the decade following Massasoit’s death, as English immigration accelerated and frayed the relationship between the two peoples, Massasoit’s son Metacom led a confederation of tribes against the Puritan colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut and their own Native allies in “The Great Narragansett War” of 1675-1676. This conflict lasted 14 months and resulted in thousands of Natives dead, hundreds more enslaved, and dozens of villages and fields burned. The English themselves lost 600 soldiers and saw 17 English settlements, including Providence, RI, destroyed.

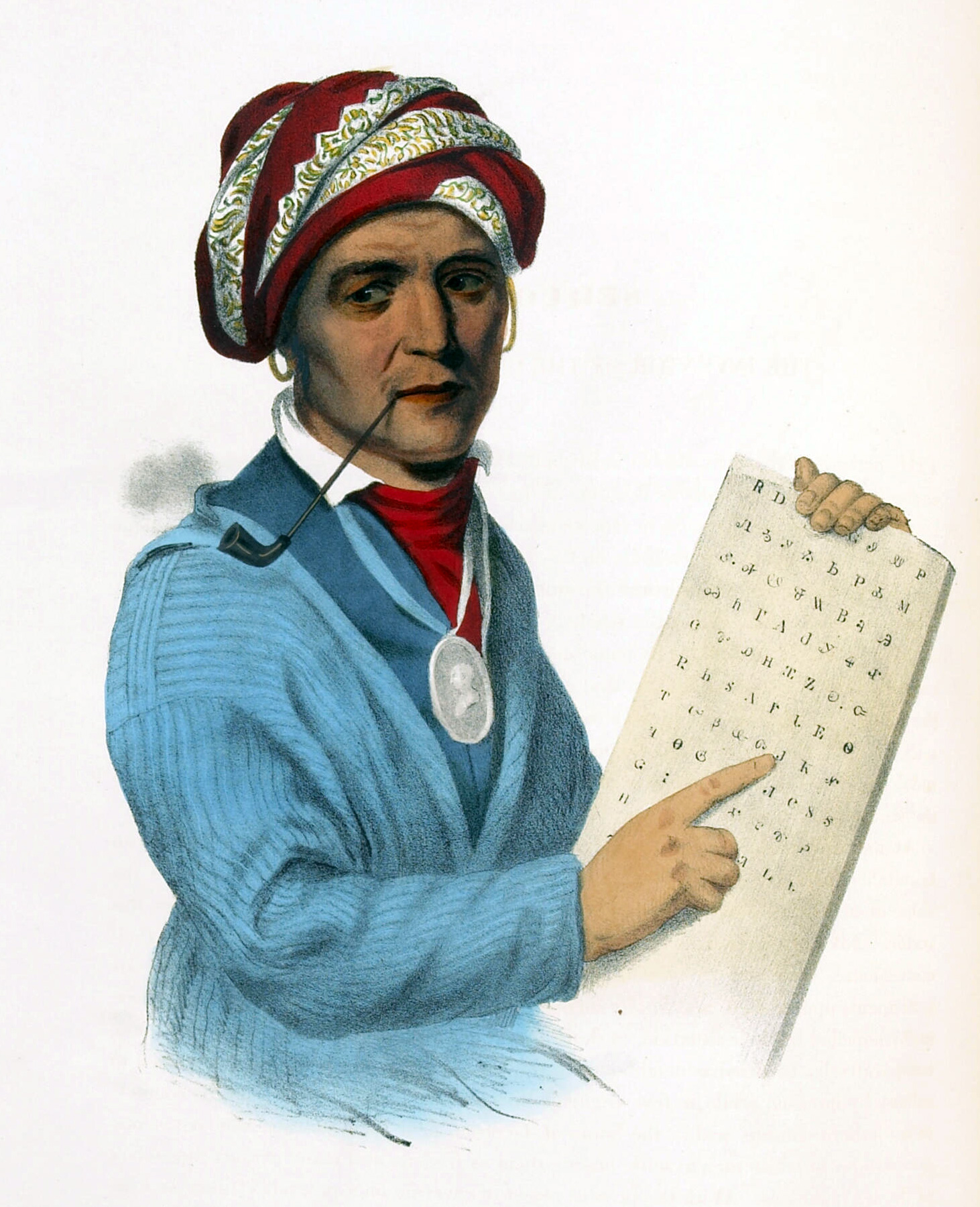

November 2: Sequoyah (George Gist), Cherokee: “Talking Leaves”

Sequoyah was born approximately in 1778, in what is now Tennessee, to a European American father and a Cherokee mother. As a young man, he worked as a trader and a smith. It is believed that around 1809 he began contemplating how to develop a written system for the Cherokee language, recognizing the power such communication gave to European Americans as he watched US soldiers communicating via their “talking leaves.” Despite disapproval by many of his countrymen and the fact that he spoke only Cherokee, he began developing a Cherokee writing system.

Sequoyah’s first attempts at written Cherokee utilized pictograms for every word, but he rejected that as too cumbersome. Eventually, aided by his daughter Ayoka, he broke down the Cherokee language into its unique syllables, realizing there were about 85 in all, he developed a symbol for each syllable, a system known as a syllabary. Although only 6 years old, Ayoka learned the syllabary. However, he and his daughter were charged with witchcraft and placed on trial. After being able to communicate to each other on paper despite being separated, Sequoyah and Ayoka were not only acquitted, but he was asked by some of the judges to teach them how to read and write. He even traveled to the Arkansas Territory, where some Cherokee had removed since the mid-1810s, and taught his system there. In 1825, the Cherokee Nation formally adopted his syllabary, and by late that year the Bible and several hymns had been transcribed in the new writing system.

The system Sequoyah devised was so simple that learners could master it in less than a week; by 1830 the Cherokee achieved one of the highest literacy rates (90%) of any people on Earth. With the assistance of Methodist missionary Samuel Worcester, the Cherokee established their own newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix, in 1828, the first bilingual paper in US history. Sequoyah developed a printed version of his handwritten syllabary to be better suited for use by printing press. He even developed written numerals, although these were rejected by the Cherokee council.

November 3: Sacagawea (Tsi-ki-ka-wi-as), Lemhi Shoshone:

Born in approximately 1788-1790 in modern Idaho among the Lemhi Shoshone, at about age 11, Sacagawea was captured by enemy Hidatsas and sold to an allied Missouri River Mandan village in North Dakota, near present-day Bismarck.

After the Jefferson administration completed the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were hired to lead a Corps of Discovery into this vast new area by traversing up the Missouri River starting at its mouth near present-day St. Charles starting in May, 1804. When winter set in, they camped near the Hidatsa-Mandan village, where French Canadian trapper Touissant Charbonneau, who lived among the villagers, had claimed the teenaged Sacagawea as one of his wives. Charbonneau persuaded Lewis and Clark to hire him as an interpreter, claiming his knowledge of Hidatsa and sign language, and his wife’s knowledge of Shoshone. Sacagawea gave birth to her first child John-Baptiste in February, and in April, 1805, the Corps, now composed of 31 men and one teenaged girl, set out again with Sacagawea’s infant carried on her back. The only other person of color among the Corps was an African American named York, who was enslaved by Clark.

Sacagawea contributed immeasurably to the success of the Corps, interpreting, augmenting their diet with edible plants she foraged, even rescuing critical instruments and supplies during a near-capsizing of one of their boats while her husband panicked. The presence of a woman and child often had the valuable psychological effect of indicating the peaceful intention of the party to new villages they encountered. When the Corps reach Shoshone land, she took charge of interpreting with their leader Cameahwait, to realize that he was her brother. After their emotional reunion, she was able to enlist much-needed Shoshone aid and support for their final push to the Pacific Ocean in November 1805. As the Corps temporarily divided into two parties for the first half of the return journey starting in March, 1806, Sacagawea then helped guide the southern party, led by Clark, back east. When the two groups reunited back in Hidatsa territory, Sacagawea and her husband and son stayed behind. Despite Clark’s praise for her invaluable assistance in his journals, she herself received no pay for her labor on behalf of the Corps. The only other unpaid Corps member was York. Clark later helped raise and educate her son and a daughter, Lisette, in St. Louis. Sacagawea died, probably of typhus, at about age 25.

In 2000, Sacagawea was the first historical woman as well as first Indigenous person (alongside her son) to appear on modern US currency. Sculptor Glenna Goodacre, who also created the sculpture for the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, used a Shoshone student named Randy'L He-dow Teton to depict Sacagawea.

November 4: Tecumseh, Shawnee/Muscogee: Orator and Unifier

On March 9, 1768, as a meteor blazed across the sign in a portent of greatness, Tecumseh, whose name means “Shooting Star,” was born in Piqua village near modern Xenia, Ohio. His father was Shawnee and his mother Muscogee (Creek). His father was killed by white in 1774, and soon after his mother left him in the care of his elder sister Tecumapease and elder brother Cheesekau as she traveled with part of the tribe to Missouri. He was later adopted by Chief Blackfish, and fought alongside him on behalf of the British in the American Revolution.

Within the first 20 years of his life, Tecumseh witnessed three transfers of claimed sovereignty over his homeland, from France to Britain to the US after the Revolution concluded in 1786, and white settlement—and attacks—exploded.

Tecumseh was living in Indiana with his younger brother Tenskwatawa, henceforth known as “the Prophet,” when that brother had a vision of restoring Native power through purging all white customs and influence and uniting in a pan-Indian confederacy stretching from Canada to Mexico. Between 1808 and 1812, Tecumseh travelled as far west as the Ozarks, north to New York, and south to Alabama attempting to persuade tribes to join him. Aided fortuitously by a comet and later the New Madrid earthquake in 1811, some tribes were persuaded.

When the War of 1812 began, Tecumseh travelled to Canada and allied with the British, who promised that if the Natives under his command helped the British win, the Old Northwest Territory would become a separate Indian nation protected by Britain. Despite capturing Detroit and fomenting a Muscogee uprising in Alabama, he and his British allies failed in an invasion of Ohio, and Tecumseh was killed after retreating into southern Ontario at the Battle of the Thames River in October 1813. He was buried secretly, and his body never found. But with his death, the last great wave of Indian resistance in the lower Midwest and South disintegrated, and US government insistence on clearing the lands east of the Mississippi River of native inhabitants intensified with little hope of resistance.

November 5: Wilma Mankiller (A-ji-luhsgi), Cherokee: Activist, Chief, Humanitarian

Wilma Pearl Mankiller was born near Tahlequah, Oklahoma, on November 18, 1945, one of eleven children raised on a farm named Mankiller Flats which had been granted to her grandfather as part of compensation for resettlement. After the farm failed when she was 10, she and her family moved to a poor neighborhood in San Francisco as part of the US government’s relocation policy that attempted to disperse tribal communities and terminate tribal governments starting in 1956. From a young age, she engaged in activism to preserve Native culture and identity, joining the newly organized Native American Rights movement.

In 1969, Ms. Mankiller participated in the American Indian occupation of the abandoned Alcatraz Island, based on ignored treaty language that returned any abandoned military forts to Native ownership. Educated as a social worker, she became director of the Native American Youth Center in Oakland and also helped the Pit River Tribe as it fought a seizure of its lands by Pacific Gas and Electric. In 1977, she moved with her two daughters back to Oklahoma to try to reclaim her family’s farm. After struggling to find work, she was eventually hired as economic stimulus coordinator for the Cherokee Nation, and founded their Community Development Department, working to build a sense of empowerment in impoverished communities that often struggled with high unemployment and a lack of infrastructure and basic services.

In 1983, Ms. Mankiller was elected deputy principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. In 1985, she became principal chief when her predecessor was appointed head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, becoming the first woman to lead a major Native American nation. During her tenure, she nearly tripled tribal enrollment; raised standards for education, health care, and housing; increased employment opportunities; and worked to reduce infant mortality. She was reelected in 1987 and 1991, serving a total of 10 years, only stepping down in 1995 due to poor health. Her honors included being named Ms. magazine’s woman of the year in 1987, induction into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1993, and receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Clinton in 1998. In retirement, she served as an advocate and speaker for social justice and Native and women’s empowerment.

Ms. Mankiller passed away in April of 2010 after a valiant struggle against pancreatic cancer.

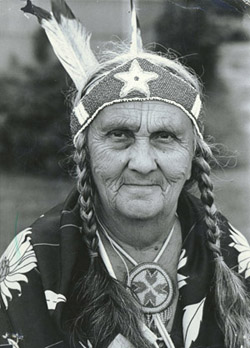

November 6: Esther Ross, Stillaguamish: Demanding Recognition

Photo courtesy of the Stillagamish Tribe of Indians, used by permission.

Esther Ross was born in 1904 in Oakland CA, the daughter of a Norwegian American father and a Stillaguamish mother. The Stillaguamish traditionally lived along the Stillaguamish River largely in Snohomish County, Washington. In 1855 the US government gathered the leaders of more than 22 tribes around Puget Sound, including Suquamish leader Chief Seattle, and concluded a treaty with them in which they relinquished the lands they traditionally claimed in the area in exchange for four reservations and fishing rights. Promises were also made orally to the tribes prior to signing by Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens. Several of the tribes who signed the treaty believed that they would be given their own reservations, including the Stillaguamish. When they learned that they would instead be required to live on a reservation with the Tulalip people, many of the Stillaguamish refused to leave their homeland, even though no longer theirs. Over the generations their population, never above more than a few hundred at best, declined.

In 1926, and by that time married and with a small infant, Esther Ross was contacted by relatives in Washington state to come and help her people file federal claims for the US government’s unfulfilled promises. Mrs. Ross learned that the federal government conveniently refused to officially recognize tribes who lacked land, as the Stillaguamish did. This meant that the 66 remaining officially enrolled members were ineligible for any of the benefits that had been delivered to larger tribes under the Point Elliot Treaty. For over 50 years Mrs. Ross became notorious for constantly calling upon government officials and loudly demanding to be heard, to the point that officials were known to hide when they heard that she was in the building.

In 1976, celebrations of the US bicentennial included a highly publicized wagon train that traveled across the continent-- and near the souvenir store that served as the Stillaguamish meeting place and center of operations. Mrs. Ross announced that the tribe would attract attack the convoy around the wagon train unless they were granted official recognition by the Department of the Interior, landless or not, noting that they had fought for their rights for nearly 50 years, and that at 70 years old she was done waiting. The story soon made international newspapers across the world and proved highly embarrassing to the US government.

On the day the wagon train was scheduled to arrive near the Stillaguamish’s traditional homeland, the secretary of the interior sent a special assistant by plane to meet Esther Ross. He promised official recognition within 30 days, but had brought no documentation, and Esther Ross knew that she and her people had been lied to repeatedly before. When the wagon train actually arrived, it was greeted by approximately 200 people blocking the road. Esther's son Frank stopped the lead horse and informed the wagon master that they weren't moving. Esther then appeared after several moments and described the wagon train as symbolizing a trail of broken promises and destructed lives for Native peoples. She then symbolically handed the wagon master a letter for the secretary of the interior and a good luck medal and allowed him to continue. And yet still the Stillaguamish remained unrecognized. Finally, in October of 1976, the federal government officially recognized the tribal government and claims of the Stillaguamish, despite being one of the smallest tribes of indigenous people in America, and a few weeks later she was named Chairman for her indefatigable work for her people.

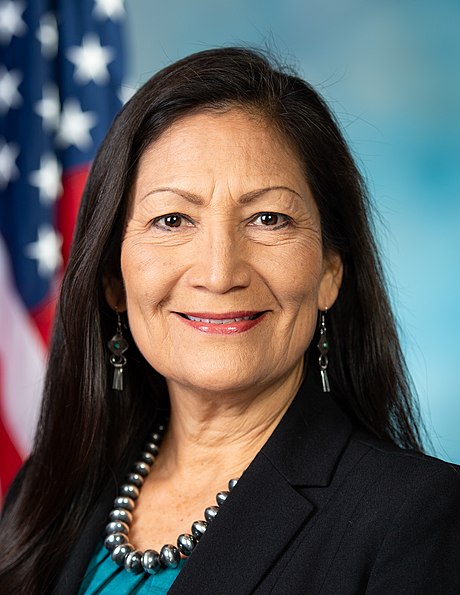

November 7: Debra Haaland, Kawaik People (Laguna Pueblo), Secretary of the Interior

Debra Anne (Deb) Haaland was born on December 2, 1960, to a Laguna Pueblo mother and a Norwegian-American father. Although born in Winslow, Arizona, she calls herself a “35th-generation New Mexican” due to the presence of the Pueblo people on these lands dating back to at least the 12th century. Both her parents served in the military, with her father’s military career moving the family frequently until they moved to Albuquerque to be near family who lived in Mesita village in the Pueblo of Laguna 45 miles to the west in the San Mateo mountains near the Continental Divide. As a young adult she attended the University of New Mexico and earned a BA in English. She gave birth to her daughter Somah immediately after graduating and started her own business to support them, struggling to avoid homelessness as well as seeking—and being denied-- SNAP benefits.

Ms. Haaland nonetheless completed law school in 2004 at the University of New Mexico, specializing in Indian law. She later served as the first female chairwoman of the Laguna Development corporation while serving as tribal administrator for the San Felipe Pueblo from 2013-2015. In 2018, she was one of two Indigenous women who became the first Native women elected to the House of Representatives, along with Sharice Davids of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Kansas. Her focus as a Congresswoman was missing and murdered Indigenous women, climate and environmental justice as well as pro-family policies. In 2021, Rep. Haaland was nominated by President Biden to serve as the first Indigenous secretary of the Interior, which oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs. As Interior Secretary, Ms. Haaland has created a new “Missing and Murdered Unit” within the Bureau of Indian Affairs to investigate the disproportionately monumental numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women and created the Federal Boarding Schools Initiative to investigate generations of Native children suffering abuse, neglect, and death at boarding schools funded through the 1819 Civilization Fund Act.

November 8 - 14: Indigenous Missouri

November 8: The Confluence Region: Rivers Run Through

For millennia, the Confluence Region of North America, where the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers and their tributaries meet, was a very attractive area for Indigenous settlement, fishing, and hunting. Rivers, creeks, and other streams attracted not just wildlife but provided water for drinking and cleaning, while the forests that once covered the eastern half of the state provided raw materials and fuel for cooking. The caves within the forests and along the streams provided ready shelter for hunter and hunted alike, and tools were made from stone, bone, and wood.

Archaeologists estimate the first human hunters in Missouri to date around 9500 BCE, drawn here by woolly mammoth and giant sloths as prey. Hunter-gathering societies are believed to have begun developing around 7,000 BCE, inaugurating what is known as the Archaic period that lasted until about 1,000 BCE. At about that time, pottery may have begun to be manufactured, inaugurating what is known as the Early Woodland period, with evidence of religious rites around burial being developed. From 5500 BCE to about 400 CE, the Middle Woodland period is characterized by the development of settlements, the domestication of plants such as corn and the development of trade, which especially flourished in eastern Missouri and southern Illinois, thanks once again to travel made easier by river. From Illinois and Missouri to the north, to Louisiana and Mississippi to the south, the Mississippi River began to support a vast trading culture centered more to the east along the Ohio known as Hopewell.

Educational sites of interest related to the earliest human presence within the boundaries of the Diocese of Missouri include Mastodon State Park in Imperial, Rodgers Shelter Archaeological Site in Benton County, the Cuiver River Complex near Troy, and Native American Petroglyphs in De Soto.

November 9: Cahokia and Mississippian Culture

From about 800 CE to 1600 CE, the banks of the Mississippi River near St. Louis were home to a flourishing great civilization known as Mississippian, which stretched from the Southeast as far as Georgia to the Midwest. The explosion in village population was literally nourished by the mixed cultivation of corn, beans, and squash known as “three-sister” agriculture, augmented by abundant game in the forests and rivers which anchored individual settlements. Food production at one point may have supported as many as 40,000 people around Cahokia alone, with their ability to support specialized trades, artisans, and religious leadership peaking around1100 CE. Satellite towns usually covered around 10 square acres, surrounded by wooden pickets. Thanks to a moderate climate, the people who lived here lived outdoors, only sleeping in their wood framed, cane-mat covered houses in winter.

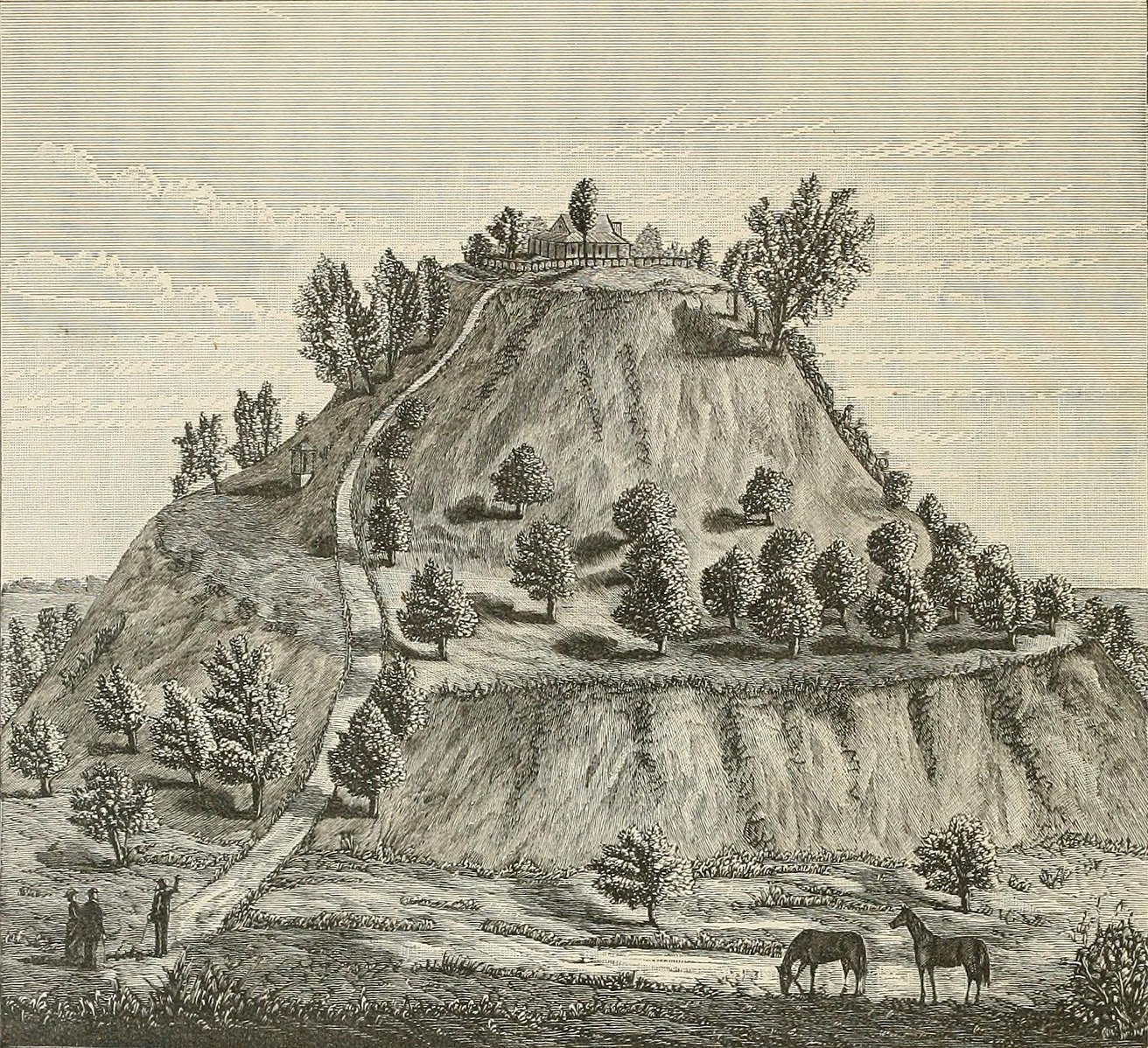

Religion and social hierarchies structured daily life once the fear of want receded. The great towns centered around ceremonial mounds that could reach 100 feet high, and thus the other name for the Mississippian culture is “Moundbuilders.” Large mounds were the location of homes for the elite ruling and religious classes. Smaller mounds were usually burial sites for more common folk. There is much speculation as to what caused the decline of Cahokia: diseases racing ahead of European settlers, carried by trade? Too much agricultural development creating erosion? No one is certain. But by the time Europeans really began making their homes here, Cahokia was largely abandoned and its culture scattered.

At one time, the greatest Moundbuilder settlement covered both sides of the Mississippi River from what is now St. Louis to Cahokia in Illinois, along the New Madrid fault. To this day, one of the nicknames for St. Louis is “Mound City” due to the prevalence of ceremonial mounds (estimated to be at least 40 in all) when the French arrived in the late 17th century. The main complex of mounds in the city of St. Louis is now the Convention center complex. Some of the mounds within Forest Park’s boundaries were finally leveled for the 1904 World’s Fair. The only partial mound that still remains on the west side of the Mississippi is Sugar Loaf Mound, located in south St. Louis city in the Dutchtown area north and east of Carondelet. Ironically, the mound has been saved from further destruction by the Osage Nation, which purchased the mound in 2009.

Educational sites of interest related to the Mississippian period in the Diocese include, of course, Cahokia Mounds in Illinois and the New Madrid Historical Museum in New Madrid.

November 10: The Osage: The People of the Middle Waters

The Wazhazhe People call themselves “The Children of the Middle Waters.” French trappers and traders who encountered them mispronounced that as “Osage.” Their language is Siouan, related to the Kaw (Kansa), Omaha, Ponca, and Quapaw who probably originated near the Ohio River but had migrated to the mouth of the Ohio by 500 CE. The forerunners of the Osage settled near Cahokia for a time, but by the time of its decline around 1350 they moved west along the Missouri River. By the late 17th and throughout the 18th centuries, aided by the arrival of horses descended from those brought by the Spanish from Europe, the Osage had moved to the eastern half of the Great Plains, from Missouri and Arkansas to Nebraska and Kansas.

Osage village life was patriarchal, divided among two main divisions, 24 clans, and numerous more sub-clans. The men headed west to hunt bison on horseback, as well as other game, from March to May, and also from July through August. In between the women planted, and then tended and harvested crops.

European Americans who encountered them remarked on the tall stature and physical strength. The Osage became sought-after allies by the rival European powers invading North America in the 18th century. In 1723 the French established Fort Orleans among the Osage near Brunswick, Charlton County, just to the west of our current diocesan boundaries, and about 125 miles due west of Calvary parish in Louisiana, the first European fort west of the Mississippi.

The resulting proximity to Europeans not only caused exposure to disease but also caused enormous competition among tribal groups to gain trade goods, especially guns. This simultaneously increased inter-tribal warfare and made it far more deadly as European settlement compressed dozens of tribes into ever smaller areas seeking game pelts to trade.

The Louisiana Purchase and subsequent encounters with the Corps of Discovery also marked the Osage’s first treaty giving up land to the Americans in 1808. When William Clark was territorial governor in 1814, he negotiated what ended up being a partial Osage removal to Kansas and now-Oklahoma. More treaties followed in 1818, and in 1824 after Missouri statehood, yet some Osage remained within state boundaries, often to hunt. Finally, in 1837, 500 Missouri militiamen expelled the remaining Shawnee, Delaware, and Osage from Missouri in the so-called “Osage War.”

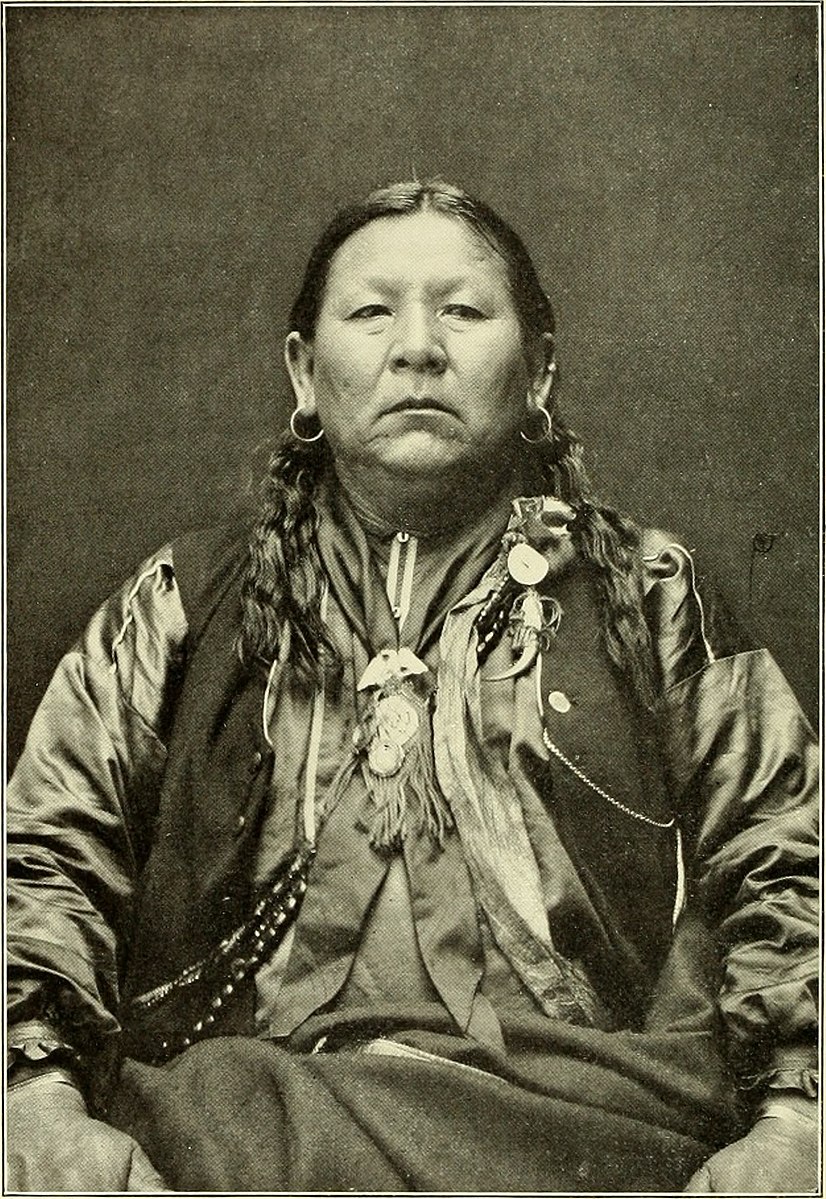

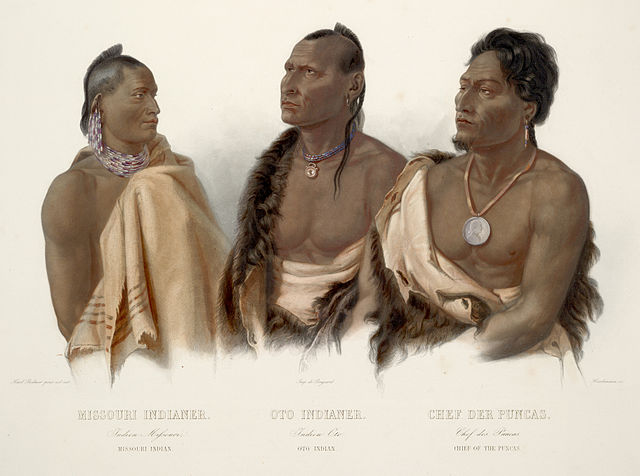

November 11: The Otoe and Missouria

In 1673, Pere Jacques Marquette and adventurer Louis Jolliet met a tribe of indigenous Siouan people who called themselves the Niutachi, numbering perhaps 10,000 people, and alongside the Osage dominated what would become Missouri. When they asked their Peoria guides the names of this people, the guides supposedly replied “Wehmehsoori,” or “the people of the wooden canoes.” The Frenchmen wrote the name “Ouemessourit” on the map, and then put it on the river where they lived too, which later was applied to the entire state.

Like the Osage, it is believed that the Missouri had once dwelled between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River with their kinsmen the Otoe, the Iowa, and the Ho-Chunks. On the movement west, the groups splintered, and the Otoe and Iowa ended up heading north toward Iowa, while the Missouri ventured slightly further toward the Missouri River itself, not far t the west of Kirksville. As they gained access to horses and guns, hunting and warfare became simultaneously more potentially successful and more deadly. For a while, they were second only to the Osage in the estimation of the Europeans. However, over the 18th century, their numbers eroded to around 1,000 due to disease when disaster struck in 1798: their longtime enemies, the Sauk and Fox tribes, ambushed a main body of the Missouria and slaughtered more than half of them. The remnants struggled to live among the Kaw, Osage, and Otoe. Smallpox broke out among them in 1805—just in time to meet the Corps of Discovery under Lewis and Clark.

The 400 or so survivors then affiliated with their kin, the Otoe people, who had once lived along the northern border of our diocese. Together, the combined Otoe and Missouri were confined to the Blue River reservation in Nebraska in 1855, a place of abject misery. In 1881 the Otoe-Missouri were removed again to a small reserve in now-Oklahoma, just across the Arkansas River from where the Osage bought their reservation. But the Missouri name lives on in the name of the river, the state—and two Episcopal dioceses.

November 12: The Iowa

The Iowa, who call themselves Bah Kho-Je (People of the Grey Snow) were, as mentioned previously, once probably affiliated with the Ho-Chunk people originally living near the Great Lakes. Their name’s meaning probably refers to the face that the smoke from their fires turned the snow covering their homes grey. And once again, the French completely changed their name. Ironic that now it is hometown St. Louisans who mispronounce the area’s French names regularly, restoring a bit of balance to the universe.

For much of the time of recorded Iowa history, they lived within or close to the modern boundaries of the state of Iowa concentrated along the Des Moines River, at one point claiming parts of Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. Their lands claims included the northwestern edge of the Diocese near Kirksville. Between 1824 and 1836, they too were forced to give up their lands to growing white settlement and reduced to a reservation on a narrow strip of land 10 miles wide and 20 miles long straddling the extreme eastern border between Kansas and Nebraska right next to Missouri. In 1883, the tribe split over conditions on the reservation. A separate reservation was created in now-Oklahoma near their old friends the Sauk and Fox. Those who remained in Kansas and Nebraska eventually became successful farmers. The Iowa of Oklahoma, however, were persuade accept the breaking up of their Oklahoma lands into individual allotments; their remaining land was opened to white settlement in a land run in 1890.

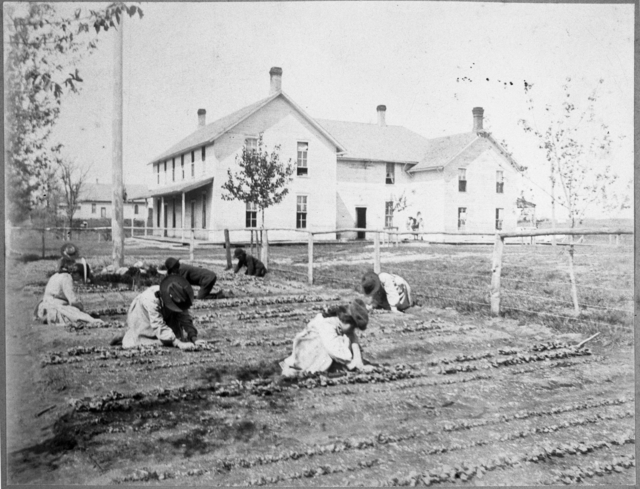

November 13: St. Regis Seminary, Florissant (1824-1831): Forced Assimilation

In 1824, Bishop of Louisiana William DuBourg established the second Roman Catholic boarding school for Native children in Florissant off what is Howdershell Road on the same land as St. Stanislaus Seminary. This boarding school operated by the Society of Jesus from 1824-1831, and was subsidized by an appropriation from the so-called “Civilization Fund Act” administered by the newly established Bureau of Indian Affairs within the US government. This subsidy was the first federal money for a Catholic “Indian school” west of the Mississippi River.

Its first five students were two Sauk boys and three Iowa boys ranging in age from approximately six to eleven. A sister school for Native girls was briefly operated from 1825-1831 by St. Rose Philippine Duchesne. Founded under the promise of educating these children, the experience there unfortunately was one of strict religious indoctrination, lack of food and other supplies, and beatings (including flaying with whips on bare backs) for misbehavior. Although originally benevolent in intent by the standards of the time, the purpose was to “civilize” the children and strip them of their culture, language, and traditions. Moreover, classroom instruction other than catechism was soon de-emphasized in order to have the boys do manual labor on the farm attached to the seminary, which was also supported by the labor of enslaved persons owned by the Jesuits. The Jesuits are now engaged in researching and acknowledging regret for their role in operating Indian boarding schools.

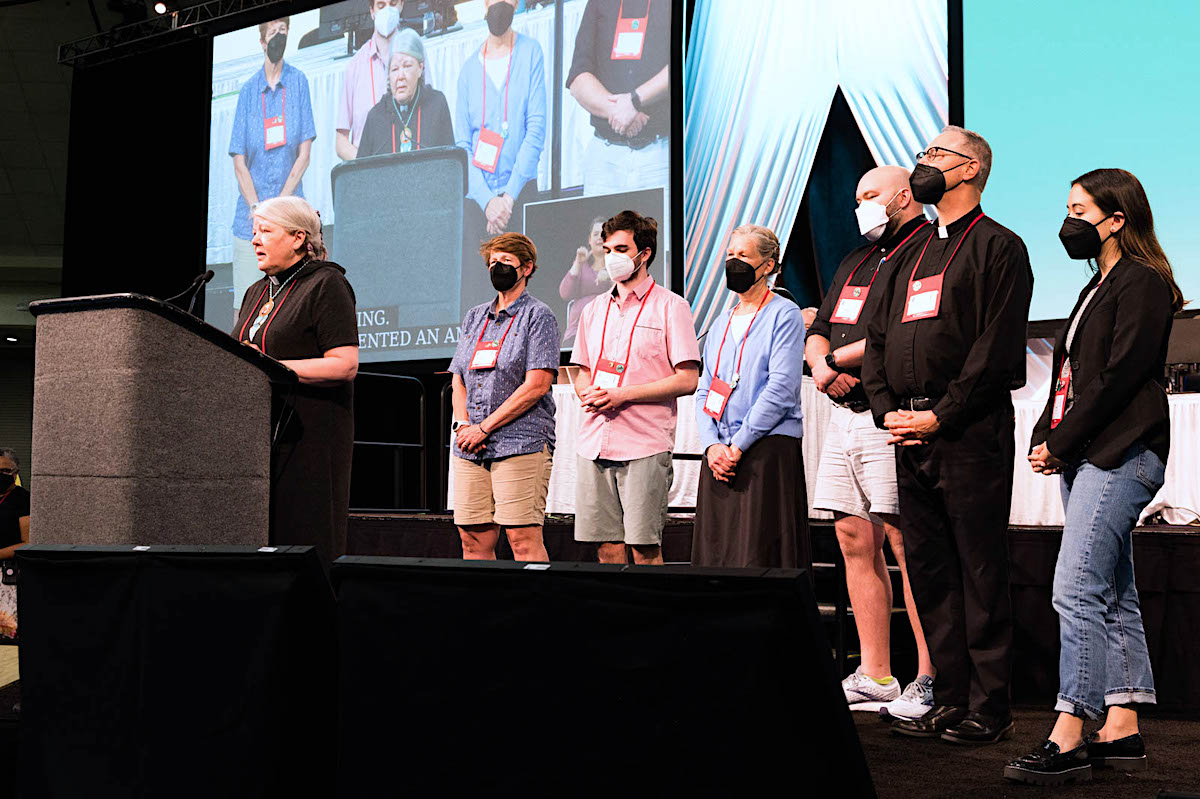

The Episcopal Church itself also supported at least eight day and boarding schools for Indigenous children in the United States. At the 80th General Convention held in Baltimore this summer, the Episcopal Church passed Resolution A127, committing resources to researching the history of the Episcopal Church in its support of boarding schools similar to St. Regis Seminary, and to acknowledge and “invest in (Indigenous) community-based spiritual healing centers that will work to address the effect of intergenerational trauma” caused by the subjection of native children to boarding schools, and to engage in education, truth-telling , and reconciliation over the Church’s complicity in supporting these institutions.

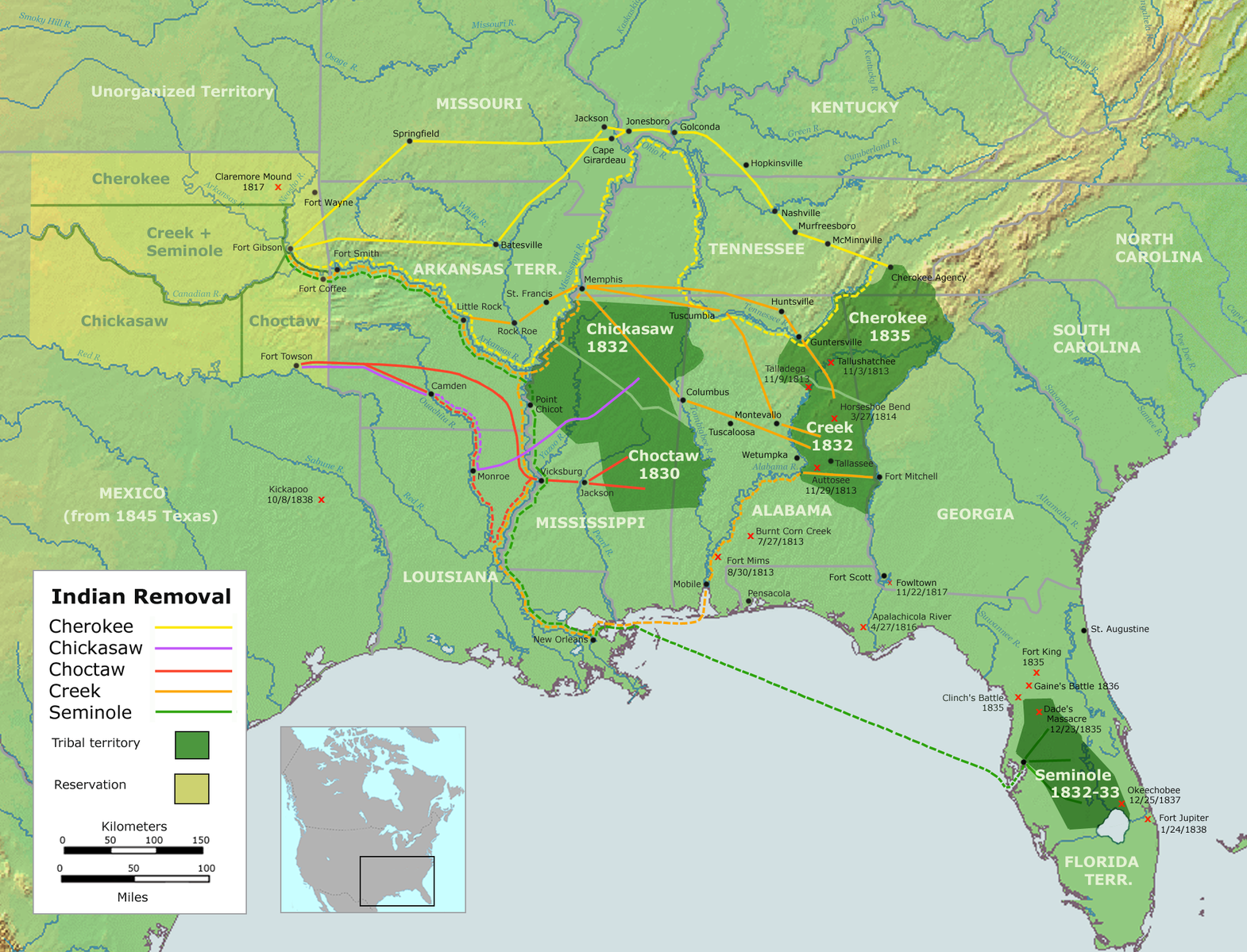

November 14: The Trail of Tears in Missouri

In 1830, after decades of pressure from Southern states, and at the urging of President Andrew Jackson, who had risen to power in part as an “Indian fighter,” the US Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the chief executive the power to exchange lands beyond the Mississippi River for tribal lands held east of the river. Even though the law did not authorize the use of force, tribal resistance from the majority of the “Five Tribes”—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole and Choctaw—led to only fragmentary removal between 1835 and 1838. They rightly pointed out that trading cultivated land with amenities for a wilderness toehold far removed from their traditional homeland was unpalatable.

In 1830, after decades of pressure from Southern states, and at the urging of President Andrew Jackson, who had risen to power in part as an “Indian fighter,” the US Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the chief executive the power to exchange lands beyond the Mississippi River for tribal lands held east of the river. Even though the law did not authorize the use of force, tribal resistance from the majority of the “Five Tribes”—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole and Choctaw—led to only fragmentary removal between 1835 and 1838. They rightly pointed out that trading cultivated land with amenities for a wilderness toehold far removed from their traditional homeland was unpalatable.

Then gold was allegedly found on Cherokee land in Georgia, and state and federal officials claimed they could no longer force squatters to respect Native sovereignty. Georgia attempted to enforce laws over Cherokee territory. The Supreme Court upheld the Cherokee Nation’s objection, but President Jackson refused to enforce the decision. The pressure was on. A fraudulent treaty was signed by a fragment of the Cherokee and swiftly ratified, the US Army was sent in to round up resisters to march them westward, in chains if necessary. Those whom they did capture were forced to travel over routes that had already been emptied of supplies by previous waves of emigres. Furthermore, the departure date of November meant the detainees would be traveling through autumn rains and winter cold. Illness and disease caused thousands of deaths.

Three of the routes taken by the Cherokee during the winter of 1838-1839 traversed through land that is now in the Diocese of Missouri. The Trail crossed the Mississippi near Cape Girardeau, and diverged at Jackson. The “Northern” route headed through Farmington toward St. James and Rolla, and then roughly followed the path of what we know as Route 66. The “Hildebrand” route approaches Ironton went nearly due west before reuniting with the Northern route near Marshfield. The Benge route veers south toward Arkansas and passes just a few miles to the west of Poplar Bluff.

November 15 - 21: Native Arts and Culture

November 15: Maria Tallchief (Ki He Kah Stah), Osage: Barrier-defying Ballerina and teacher

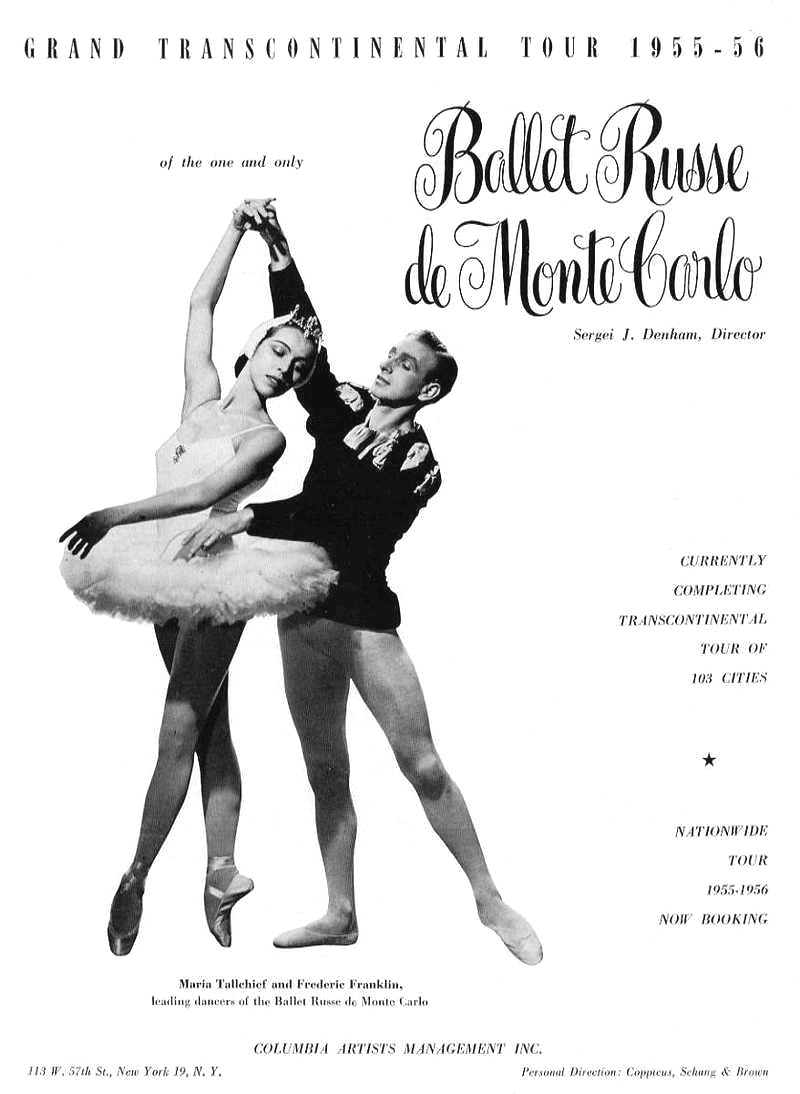

Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief (Ki He Kah Stah) was born in Fairfax, Oklahoma, on the Osage Reservation, in 1925. Both she and her sister Marjorie displayed an early talent for dance, and received lessons thanks to her father’s wealth from petroleum royalties. After her family moved to Los Angeles to expand her opportunities when she was 8, Ms. Tallchief moved to New York after graduating high school. She joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo as an understudy, and then received positive reviews for her first performance in 1942. She was the first American to dance with the Paris Opera Ballet in 1947, as well as the first American to dance at the Bolshoi Theatre in 1960.

Despite pressure to “Russianize” her name for fear that contempt for Native Americans would derail her career, she embodied both artistic excellence and pride in her heritage. After dancing as Betty Marie Tallchief in Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo, she accepted de Mille’s suggestion to use “Maria Tallchief” as her stage name. Her sister, a star ballerina in Europe, also adopted the single-word last name. In 1946, she married famed choreographer George Ballanchine. Her signature roles were of the Firebird, which Ballanchine created for her, and the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker. Ms. Tallchief also appeared in the 1952 film “Million Dollar Mermaid” as Anna Pavolova. After retirement from dancing, she opened the Chicago City Ballet school attached to Chicago’s Lyric Opera with her sister, and became an esteemed teacher.

Although one of five remarkable ballerinas of Native ancestry in the mid-20th century, along with her sister Marjorie as well as Yvonne Chouteau (Shawnee), Rosella Hightower (Choctaw Nation), Moscelyne Larkin (Peoria/Eastern Shawnee), she was acclaimed as one of the most brilliant ballerinas of the 20th century. She received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1996. She was also the mother of poet Elise Paschen. She passed away in 2013 at age 88.

November 16: Joy Harjo, Muscogee (Creek) Nation: Artist, Poet Laureate of the United States, and musician

Born Joy Foster in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1951, this award winning poet and acclaimed musician changed her name to Harjo to honor her Muscogee grandmother’s family name. Joy Harjo recently completed three terms as the 23rd poet laureate of the United States. She also has Cherokee heritage through her mother. After overcoming childhood abuse from her father and stepfather, she first expressed herself through painting, and attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe while a teenager. She also played saxophone and sang in an all-Native rock band while there; she played saxophone and flute as well as singing and performing spoken word pieces with a band named Poetic Justice, as well as her current band called Arrow Dynamics.

She has taught at the University of New Mexico, University of Illinois campus in Urbana, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the Institute of American Indian Arts. She has received numerous awards and honors, including the Lilly Prize, the Griffin Poetry Prize, the Wallace Stevens Award, the PEN Literary Award for her memoir, the American Book Award, the William Carlos Williams Award, the Oklahoma Book Award, the lifetime achievement award from the National Art Awards, induction into the National Native Hall of Fame, being declared an “Oklahoma Cultural Treasure.” She currently serves as the first Artist-in-Residence at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, OK. A strong sense of justice, empowerment, history, and musicality informs her writing. Her nine books of Poetry include In Mad Love and War (1990), Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings (2015) and An American Sunrise (2019). Her signature project as US Poet Laureate was Living Nations, Living Words, an introduction to Native poets that includes a published anthology.

Notable poems by Ms. Harjo include “She Had Some Horses,” “Once the World Was Perfect,” “Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings,” “This Morning I Pray for My Enemies,” and “Eagle Poem,” many of which can be found and enjoyed online at the websites for The Poetry Foundation and the American Academy of Poets.

November 17: The Deloria family, Standing Rock/Yankton Sioux: Historians, scholars, activists

The Deloria family are literally a force of nature among Native intellectuals. Philip Deloria is the 2022 president of the Organization of American Historians and the first tenured Native American professor at Harvard University. Two of his books deal with Native identity and stereotypes: Playing Indian addresses non-Native people appropriating Native cultural aspects, while Indians in Unexpected Places addresses the imaginative expectations that only conceive of Native people as living on reservations and shunning current culture.

Philip’s father, Vine Deloria, Jr., born into the Yankton Sioux, was a lawyer, theologian, professor of political science, law, and Indian studies and is a noted Native scholar, author, and activist. He was the executive director of the National Congress of American Indians from 1964-1967, and has served as an expert witness in trials regarding Native subjects. His first of his 20 books, the 1969 cultural proclamation Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, explained the historical and intellectual foundations of the Indian Rights Movement that flourished within and alongside the broader Civil Rights Movement. The library at the National Museum of the American Indian is named in his honor. He died in 2005.

Philip’s uncle, Philip S. “Sam” Deloria, was director of the American Indian Law Center at the University of New Mexico’s law school and an expert of federal Indian policy. Philip’s grandfather, The Rev. Vine Deloria, Sr. (1901-1990), and great-grandfather, The Rev. Philip Joseph Deloria, also known Tipi Sapa, or Black Lodge (1853-1931) were Episcopal priests serving the Lakota people. Philip’s great-aunt, Ella C. Deloria (Angpetu Washte Win, or Beautiful Day Woman), who lived from 1889-1971, was an ethnographer and linguist. She attended Oberlin College and Teachers College, Columbia University, and was an instructor at Haskell Indian Boarding School (now Haskell University) in Lawrence KS, as well as working at the Sioux Indian Museum and the W. H. Over Museum in South Dakota. She was fluent in the Dakota, Lakota, English, and Latin languages, and was the pre-eminent ethnographer of the Sioux people, working on a Lakota dictionary at her passing. Her sister, Susan Deloria, known as Mary Sully (1896-1963), was an abstract and avant-garde artist specializing in triptychs of public figures. Philip has written a book about her works and career.

November 18: Louise Erdrich, Turtle Mountain band of Ojibwe: Novelist, poet, and Pulitzer Prize winner

Karen Louise Erdrich was born in 1954 in Little Falls, Minnesota, but grew up in Wahpeton, Minnesota, where her Chippewa mother and German-American father both taught at what is now Circle of Nations Wahpeton Indian School, then controlled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She attended Dartmouth as an undergraduate in the first class to admit women, and earned a master’s degree from Johns Hopkins. Her sister Heid E. Erdrich is also a poet and author.

Most of her novels have dealt with Ojibwe characters and settings. Her first four books centered around the fictional town of Argus, North Dakota, with overlapping characters. Her novel The Round House won the National Book Award in 2012; The Night Watchman inspired by her mother’s father, won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 2020. She has also published the short story collection The Red Convertible and three books of poetry. Her poem, “Indian Boarding School: The Runaways,” from Original Fire: Selected and New Poems is particularly powerful for those interested in the current attempts to reckon with abuses and deaths at boarding schools in the US and Canada.

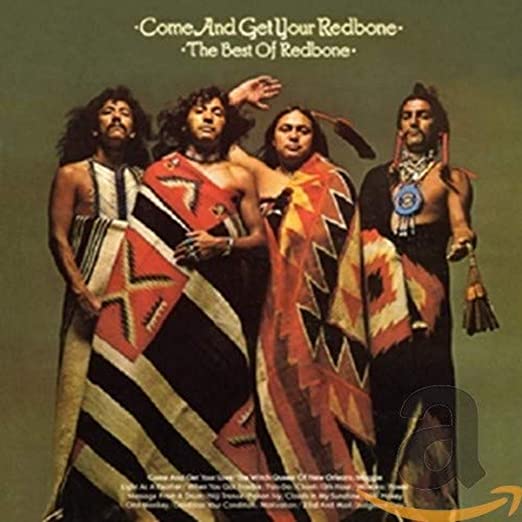

November 19: Redbone, Yaqui, Yaqui/Shoshone, Southern Cheyenne/Turtle Mountain Chippewa

Redbone was founded by brothers Pat and Lolly Vasquez-Vegas, in 1969 in Los Angeles, with the peak of their career running through 1977. It was the first band of Native Americans to have a top five hit single on the Billboards charts, with the song “Come and Get Your Love, which experienced a resurgence after being prominently featured in the film and soundtrack for Guardians of the Galaxy in 2014. In 1973, their single “We Were All Wounded at Wounded Knee” was released but banned from most US radio stations’ playlists due to its political content, although the song charted overseas.

During their peak, all of the members of the band were of Native American and Latino descent; the name “Redbone” is a Cajun term for those of mixed-race ancestry. Bassist/Vocalist Pat and Guitarist/Vocalist Lolly Vasquez-Vegas were of Mexican American and Yaqui-Shoshone ancestry. Lead guitarist Tony Bellamy was of Yaqui ancestry. Drummer Peter (Last Walking Bear) DePoe was of Southern Cheyenne, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, and Rogue River Siletz ancestry. Between 1970 and 1974, Redbone released a series of albums whose songs dealt with Native themes, including Potlatch (1970), Message from a Drum (1972), Already Here (1972), Wovoka (1974), and Beaded Drums Through Turquoise Eyes (1974).

November 20: Jones Benally and family, Dine (Navajo): Hoop dancers, singers, and musicians

Jones Benally is a traditional Dine (Navajo) healer and hoop dancer from Black Mesa, Arizona. His exact age is uncertain, although he is believed to be in his 90s. Jones’s reputation as a healer is so respected that he was employed by the Indian Health Service at their Winslow, Arizona facility to work alongside western- medicine practitioners. Together with his children, Jeneda (born 1974), Klee (born 1975), and Clayson (born 1977), and now grandchildren, he has sung, drummed, and performed internationally, including at the Library of Congress.

Klee, Jeneda, and Clayson also formed the punk rock band Blackfire in 1989. Jeneda and Clayson also perform as a bass and drum duo known as Sihasin (which means “Hope.”). As Jones’s children were growing up, to avoid being sent to boarding school, they moved to Flagstaff, on the border of the Dine reservation, but refused to accept relocation housing. It was there that Jones’ children first personally encountered discrimination for their Native heritage. The mockery they encountered there fueled their performance of punk rock music. They chose the name “Blackfire” after seeing smoke rise from a Peabody Coal Mine in Black Mesa. Clayson has also been an actor. In all their artistic pursuits, however, they try to follow what the Dine people call Hozho, The Beauty Way, expressed in this prayer:

In beauty I walk

With beauty before me I walk

With beauty behind me I walk

With beauty above me I walk

With beauty around me I walk

It has become beauty again

It has become beauty again

It has become beauty again

It has become beauty again

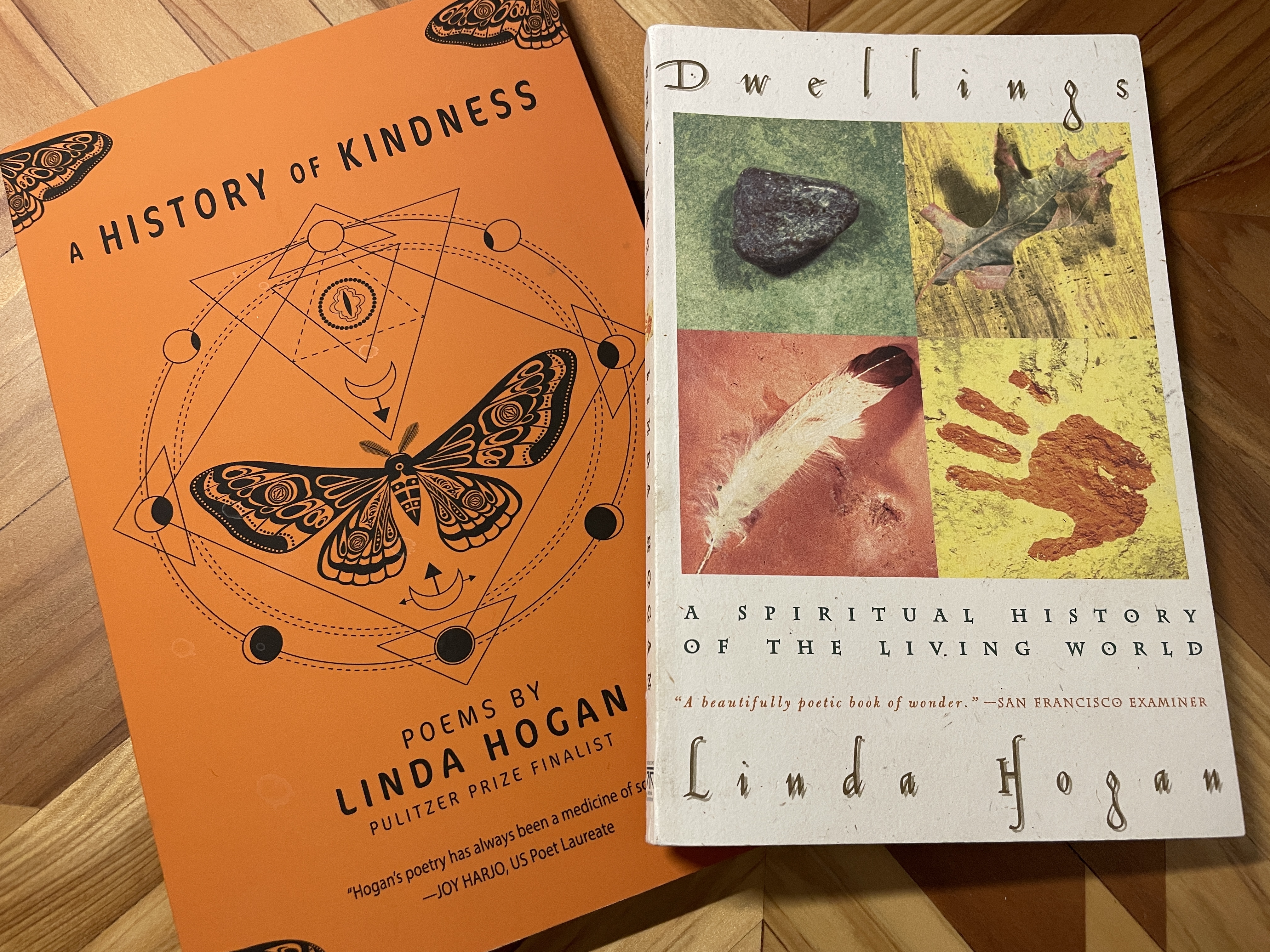

November 21: Linda Hogan, Chickasaw: Poet, teacher, environmentalist, essayist, novelist

Linda Hogan was born Linda K. Henderson in 1947 in Denver, Colorado. Her father was a Chickasaw; her uncle Wesley Henderson helped organize Native Americans who had moved to Denver as part of the federal government’s policy of relocation in the 1950s, and he was an important influence in keeping her connected with her identity as a Native American. She has served on the faculty of the Indian Arts Institute, Colorado College, the University of Oklahoma, and at the University of Colorado, Boulder. She currently serves as Writer in residence for the Chickasaw Nation in Tishomingo, Oklahoma.

Prominent themes in her work across genres include Native spirituality, environmentalism, justice for Native peoples. In 1991 she was both a Guggenheim Fellow and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Literature for her novel Mean Spirit. Her poetry is lyrical, spiritual, compassionate, embracing both the magic and the mournfulness of someone who thinks of herself as a “watcher of the world.” In her poem “The Pine Forest Calls Me,” from her latest book of poetry entitled A History of Kindness (2020), Ms. Hogan writes:

I know prayers rise with smoke

the way some people

are so perfectly uplifted

from their first roots.

But when this life of trying is finally over,

bring to my bed a small branch

smelling of green forest, the melting pure water of snow,

these mysteries discovered

one more time.

November 22 - 28: Indigenous Leaders in the Episcopal Church

November 22: Kamehameha and Emma, Kanaka Maoli: Saints and Protectors of the Hawai’i

King Kamehaha IV was born Alexander Liholiho in Honolulu in 1834. His uncle was King Kamehameha III, who adopted him as a toddler and named him heir to the throne. He was educated by Congregationalist missionaries—at that time many Hawai’ians had become Christian, and the main missions were run by either Congregationalists or Roman Catholics. On a trip at age 15 to England it is believed he became attracted to the Church of England. Alexander inherited the throne at age 20 when his adoptive father died in 1854 and took the name Kamehameha IV. A year later he married his old schoolmate Emma Rooke, who became his queen. Although they were married in Kawaiaha’o Church, which was Congregationalist, they wed in an Anglican service- the first in Hawai’i. In 1858, they had their only child, a son, named Albert Edward after the Prince of Wales. Queen Victoria was to be his godmother; unfortunately, he died at age four.

Their reign was marked by championing the well-being of their people. Concerned about the spread of disease among the Hawai’ian population, Kamehameha and Emma attempted to establish free healthcare including public hospitals. When this was vetoed by the legislature, Emma supposedly went from house to house collecting the funds and founded the Queen’s Hospital in 1859, as well as a sanitarium for lepers on Maui.

In 1860, Kamehameha IV contacted the Bishop of Oxford and Queen Victoria and requested Anglican missionaries be sent to Hawai’i. With joint approval of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the American Episcopal Church through the Bishop of California, Thomas Staley was commissioned as bishop at Lambeth chapel and sent to the islands. After Kamehameha and Emma were confirmed, other native leaders left the Congregationalists to join the Anglican Church. The king personally translated the Book of Common Prayer into Hawai’ian, and donated land for the building of the Cathedral Church of St. Andrews.

Although his reign was brief, he and Queen Emma strove to promote the good of their people and resist the annexation of Hawai’I by the US, which was encouraged by the white planter class to avoid tariffs on sugar. In 1863, Kamehameha IV died at just age 29. Emma lived on until 1885, devoting herself to good works and establishing schools under the banner of the Anglican Church. They are recognized in the Church calendar on November 30.

November 23: David Pendleton Oakerhater, Cheyenne: Deacon of the Southern Plains

The young man who would be known as David Oakerhater was born in 1847 among the Cheyenne as raised traditionally as a warrior. He completed the Sun Dance at the young age of 14, after which he was called O-kuh-ha-tuh, translated as either Sun Dancer or Making Medicine. He began his military career among his people immediately thereafter. often fighting with Comanches under Quanah Parker on the Southern Plains. After the Red River War, he was forced to surrender to US troops at Fort Sill in 1875. He was among 74 prisoners randomly sent to Fort Marion, Florida to be imprisoned under the watch of First Lieutenant, later Captain, Richard Pratt. Pratt sought to Americanize his prisoners and treat them with dignity, educating them and placing them under military discipline. At the end of two years, Oakerhater emerged proficient in English and with a talent for art. In 1877 an Episcopal deaconess from New York named Mary Burnham sponsored the prisoners to serve as church sextons, and a year later they were freed.

Deaconess Burnham persuaded Ohio Senator George Pendleton and his wife to pay for Oakerhater to be reunited with his wife and brought to New York to St. Paul’s Churhc in Paris Hill. The priest there, the Rev. J. B. Wicks, continued Oakerhater’s education, and he sought baptism six months later, adopting the first name David and the last name Pendleton in honor of his benefactors. He was ordained a deacon in 1881, and sent with Rev. Wicks to Indian Territory and Dakota Territory to recruit students for Carlisle Indian School, where Capt. Pratt had been named superintendent. Operating from El Reno and Anadarko in western Indian Territory, Oakerhater worked as a missionary among the Cheyenne, establishing missions at Bridgeport in 1887 and the Whirlwind Mission near Watonga in 1889, working to educate and evangelize his people.

Oakerhater retired from missionary work in 1918, but continued with preaching and service until he passed away in 1931. After the Dust Bowl and World War II halted mission work, the Whirlwind mission was not revived until the 1960s. St. Paul’s Cathedral in Oklahoma City organized an Oakerhater Guild and named a chapel in his honor. Deacon Oakerhater was recognized as the first Native within the Episcopal Calendar of Saints in 1985; his feast day is September 1.

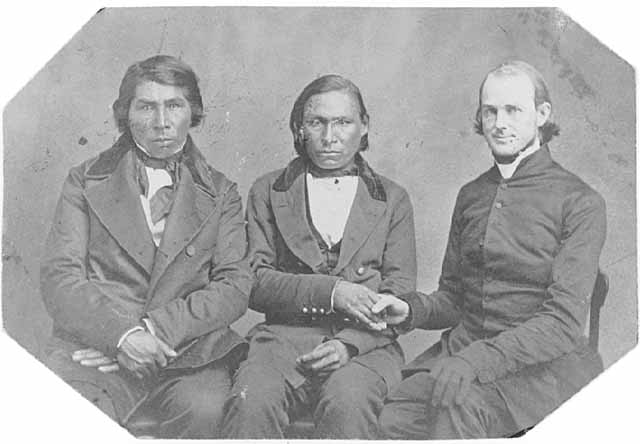

November 24: Enmegahbowh, Ojibwe/ Chippewa: Missionary and first Native Episcopal priest

Enmegahbowh was born ca. 1820 near Peterburgh, Ontario, Canada, a member of the Ojibwe people, who are also known as Chippewa in the US. His name means “He That Stands for His People.” Although his grandfather trained him in Grand Medicine Lodge (Midewiwin) religious practices, his village was supported by Methodist missionaries, and his mother was a Christian. In 1832 he traveled with Methodists to attend school in the extreme north of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and became a Methodist missionary in the US. After 1835 he served the Methodists as an interpreter and for the next ten years worked among the Natives in Michigan and Minnesota. In 1845, however, he met Episcopal priest Ezekiel Gear and joined the Episcopal Church. After baptism he took the name John Johnson Enmegahbowh.

In 1852 he helped establish the St. Columba Mission among the Mille Lacs band on Gull Lake in Crow Wing, Minnesota. This was the first Native American church west of the Mississippi in the US. After the log church was burned to the ground in the Dakota War of 1862, the mission was later moved to the White Earth reservation. During this war, Enmegahbowh, as a man of peace, warned the community of Fort Riley about the coming Native attacks, and later helped inspire peace between the Ojibwe and Dakota peoples.

In 1859 he was ordained a deacon and in 1867 a priest by Bishop Jackson Kemper, and he served and was supported by the Rt. Rev. Benjamin Whipple, first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Minnesota, at its founding in 1859. He trained many deacons during his ministry, and also helped establish the Ojibwe excellence at hymn singing. He was the first Native American priest in the Episcopal Church. He passed away in 1902, and was buried at St. Columba’s. Enmegahbowh is commemorated in the calendar of the Episcopal Church on June 12. In 2012, his Bible was restored and is a treasured relic on display at St. Columba's Church, which still exists today and holds the White Earth Pow Wow in his honor at that time each year.

November 25: Owanah Anderson, Choctaw: Author, Feminist, Native Advocate and Activist, Historian

Owanah Patricia Anderson was born in 1926 in Boswell, Choctaw County, Oklahoma. She read every book in the local library growing up, and attended the University of Oklahoma, where she earned a degree in journalism. Raised a Baptist, she became an Episcopalian when she married her second husband and lived in Wichita Falls, Texas.

Recognized among her Choctaw people as a chief, and active on the national stage in women’s and indigenous issues, Ms. Anderson pushed for attention to indigenous women’s specific issues throughout her life. She served on the board of the Association of American Indian Affairs, where she directed the National Women’s Development Program. In 1978 she was appointed to the National Advisory Committee on Women, where she worked alongside Eleanor Smeal, Ann Richards, and Bella Abzug.

Ms. Anderson was invited by Presiding Bishop Edmond Browning to chair the National Committee on Indian Affairs at the Episcopal Church Center in New York from 1983-1998. She also published two crucial resources on the history of the Episcopal Church with Indigenous peoples from an Indigenous perspective: Jamestown Commitment: The Episcopal Church and the American Indian in 1988, and 400 Years: Anglican/Episcopal Mission Among American Indians in 1997, both published by Forward Movement. She also wrote 100 Years: Good Shepherd Mission in the Navajo Nation, 1892-1992.

When schism tore at the bonds of the Diocese of Ft. Worth beginning in 2008, Ms. Anderson formed “North Texas Remain Episcopal,” one of the early groups resisting the exodus from the Episcopal Church. Starting on February 15, 2009, he also created and published 500 issues of a newsletter for “the Northern Deanery Episcopalians in the Reorganized Diocese of Ft. Worth” known as JOYFUL Notes, whose mailing list included Presiding Bishop Katherine Jefferts Schori and readers across the Episcopal Church and even to New Zealand. Owana Anderson passed away in 2017. According to her friend Katie Sherrod, at Ms. Anderson’s funeral, “We all laughed at her funeral when Bishop Steve Charleston said we should say a prayer for God, because Owanah was already explaining to God what needed to be done.”

November 26: Carol Joy Walkingstick Gallagher, Cherokee: First Indigenous female Bishop in the Anglican Communion

Born Carol Joy Walkingstick Theobald in San Diego in 1955; her mother was an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation, and her father was a Presbyterian elder. She joined the Episcopal Church with her husband after their first child was born. In 1990, she was ordained a priest and served parishes in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

At her election as bishop suffragan in the diocese of Southern Virginia, where she served from 2002-2005, she became the first Indigenous woman to serve as a bishop in the world-wide Anglican Communion. She was consecrated in April 2002 by the Rt. Rev. Robert Rowley, assisted by the Rt. Rev. David Bane and the Rt. Rev. Barbara Harris. She later served as assistant bishop in the Diocese of Newark in 2005-2007, in the Diocese of North Dakota from 2008-2014, in the Diocese of Montana from 2014-2018. Since 2018, the Rt. Rev. Gallagher has served as Regional Canon for the Central Region in the Diocese of Massachusetts. She also currently provides pastoral support in assistance to the Diocese of Albany as it implemented General Convention resolutions on making available same-sex marriage liturgies.

As an author, Bishop Gallagher has written Reweaving the Sacred: A Practical Guide for Challenged Congregations, on congregational development; and Family Theology: Finding God in Very Human Relationships, on the role families can play in faith development.

November 27: Rev. Rachel Taber-Hamilton, Shackan First Nation

Rachel Taber was born in 1964 in Ohio. Her mother’s ancestry included Shackan First Nation people from British Columbia. After searching for her own religious identity—at one point nearly taking vows as a Roman Catholic nun with an Master’s of Divinity from Loyola University’s seminary-- she joined the Episcopal church in 1995.

At her ordination in 2004, The Rev. Taber-Hamilton became the first Native woman ordained a priest in the Diocese of Olympia, where her husband is also a priest. She is trained as an anthropologist, has served as a chaplain in the healthcare field, and is currently the rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in Everett Washington.

She is also active in the fight against climate change and served on the Presiding Bishop’s delegation to the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference. She is chair of the House of Deputies Legislative Committee on Stewardship and Care of Creation. She also co-founded the grassroots advocacy group Circles of Color for people of color in the Diocese of Olympia. In July 2022 at the 80th General Convention of the Episcopal Church, Rev. Taber-Hamilton was elected the first Native woman to serve as vice-president of the House of Deputies.

November 28: Rt. Rev. Stephen Tsosie Plummer, Navajo: First Dine Bishop

Stephen Tsosie Plummer was the first bishop of Dine (Navajo) ancestry in the Episcopal Church. Born in Coal Mine, Arizona, in 1944, the son of a traditional medicine man, he was encouraged to study for ordination by the then-Rev. Harold Jones, who had been the vicar of the Mission at Ft. Defiance and later became the first Native American bishop in the Episcopal Church.

In 1975, Rev. Tsosie Plummer was ordained a deacon, and then ordained a priest in Canyon de Chelly, a sacred locale for the Dine. He served the Navajoland Area Mission as a priest from its founding in 1978. Geographically and culturally, Navajoland overlaps part of the dioceses of Utah, Arizona, and Rio Grande (in New Mexico) on the Navajo Reservation. In 1990 he was the first elected bishop of Navajoland—previously bishops had been appointed. He was an advocate for Native issues within the wider Church and urged incorporation of Navajo traditions within worship, even establishing what was termed a “hogan seminary” known as the Hogan Learning Circle to impart deeper religious education. Bishop Plummer even maintained a small flock of sheep with his wife at his home at St. Christopher’s Episcopal Mission in Bluff, Utah.

In 2000, Bishop Plummer was diagnosed with lymphoma, and he passed away in 2006.

November 29 - 30: General Convention Resolutions and Additional Resources

November 29: Recent Resolutions from General Convention on Indigenous Subjects

A great starting place for the attest information about the Episcopal Church’s engagement with Native people is the Office for Indigenous Ministries, whose Missioner is the Rev. Dr. Bradley Hauff, who is an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe of Pine Ridge, South Dakota. On that page you will find a variety of presentations and news articles on various topics of interest.

The Episcopal Church’s expanding engagement and advocacy for Native issues is a growing development over the last several years. One ongoing area of education and advocacy regards the historical attempts at the mandated assimilation of Native children through our support of boarding schools in the 19th and 20th centuries, which often led to abuse, illness, and death. At least eight of these schools have been verified to have affiliations of some kind with the Episcopal Church. Episcopal leadership is also committed to engaging with Indigenous people regarding initiatives in creation care and environmental justice, as well as anti-racism work. Resolutions passed at the 80th General Convention this summer in Baltimore that address Indigenous issues include A127, seeking truth-telling about the boarding school era; A140 supporting the creation of Indigenous Peoples’ Day; A141 supporting the creation of liturgical materials for Indigenous people; D080 to provide for the members of the Diocese of Navajoland to elect their own bishops; and D081 highlighting the ongoing crisis of missing and murdered Native women and women of color; not to mention the election of the first woman of Native ancestry, the Rev. Rachel Taber-Hamilton, as vice president of the House of Deputies.

If you would like to schedule a presentation on topics of Indigenous engagement, please contact The Rev. Leslie Scoopmire, rector of St. Martin’s Church in Ellisville and Missioner for Indigenous Engagement for the Diocese.

November 30: General Books and Websites

The honoring of Indigenous Peoples, their wisdom, and cultures, cannot be and should not be contained to a single month. Here is just a sampling of resources where you can explore a deeper knowledge of and appreciation for Native subjects and cultures:

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Carl H. and Eleanor Chapman, Indians and Archaeology of Missouri, Revised Edition (Missouri Heritage Readers Series). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1983).

Joan Gilbert, The Trail of Tears Across Missouri (Missouri Heritage Readers Series). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press,1996.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Osage in Missouri (Missouri Heritage Readers Series). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1997.

Michael Dickey, People of the River’s Mouth: In Search of the Missouria Indians (Missouri Heritage Readers Series). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2011.

R. David Edmunds, ed., Enduring Nations: Native Americans in the Midwest. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Ward Churchill, Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco: City Lights Nooks, 2004.

Timothy R. Pauketat, Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi (Penguin Library of American Indian History). New York: Penguin Group, 2009.

Angie Debo, And Still the Waters Run: the Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984.

Owanah Anderson, Jamestown Commitment: The Episcopal Church and the American Indian. Cincinnati: Forward Movement Publications, 1988.

Owanah Anderson, 400 Years: Anglican/Episcopal Mission Among American Indians. Cincinnati: Forward Movement Publications, 1997,

Heid E. Erdrich, New Poets of Native Nations. Minneapolis: Greywolf Press, 2018.

Tags: News / Indigenous Ministry Engagement